http://nautil.us/issue/29/scaling/why-you-didnt-see-it-coming

You don’t see it coming. You probably couldn’t if you tried. The effects of large changes in scale are frequently beyond our powers of perception, even our imagination. They seem to emerge out of nowhere: the cumulative effects of climate change, the creation of a black hole, the spookiness of quantum mechanics, the societal tipping points reached when the rich have billions rather than millions—even the sudden boiling of water in a slowly heating pot.

More or less of almost anything can change nearly everything.

I’ve been pondering this a lot recently as I watch the explosion of mini-mansions in my once modest Santa Monica neighborhood. A run on teardowns has left older homes looking like abandoned toys wedged between grand new structures straining at the seams of their property lines. They tower into the trees, the better to catch a glimpse of ocean, casting shadows, blocking light.

I also see a lot more dog poop on the sidewalk, a lot fewer old folks strolling at dusk, a noticeable decrease in the number of “hellos” from the neighbors. More and more owners aren’t from around here; the house down the street is for sale by Berkshire Hathaway. A little money can spruce up a neighborhood. Vast infusions of wealth can turn it into something else entirely.

None of these trends are entirely new. But the phase change I’m seeing shocked even me—and I’ve spent the past 30 years writing about the underlying math and science of precisely how quantitative changes can produce such dramatic changes in quality. My all-too-human intuitions find it hard to accept what physicist Phil Anderson made clear decades ago: “More is different.”

Making Good Use of Bad Timing

Suppose a woman suffering a headache blames it on a car accident she had. Her story is plausible at first, but on closer examination it has flaws. She says the car accident happened four weeks ago, rather than the six…READ MORE

The realm of the massive is the realm of the round, because gravity crushes everything.

Both $1 million and $1 billion sound like “a lot,” so it’s not immediately clear how such changes in wealth might also change what a builder sees as a “big enough” house. Even those who understand the true scale of the chasm between those numbers intellectually don’t always “get it” viscerally. It feels like the difference between a million and a billion is closer to a factor of three than a factor of 1,000. That’s because our brain naturally works using something like a logarithmic scale, so that it can condense information like vast ranges in loudness and brightness efficiently.

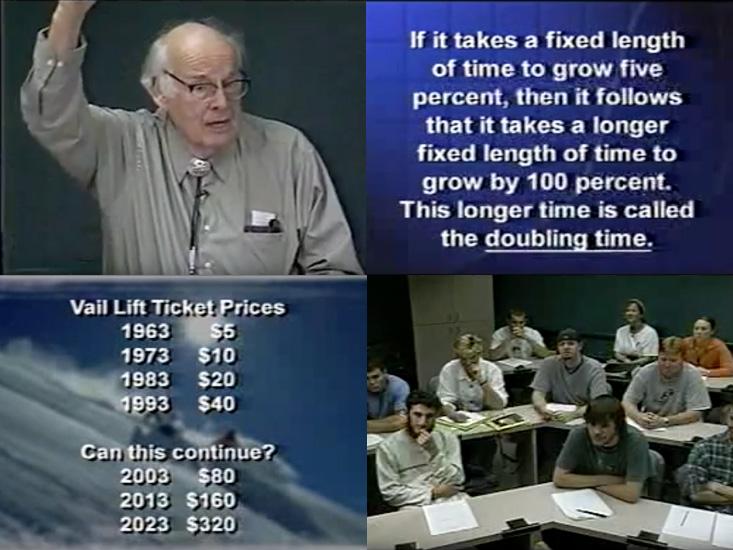

That can get us into trouble—coming to grips with pressing environmental problems, for example. The late physicist Albert Bartlett was concerned that people didn’t fully comprehend the consequences of exponential population growth and the inevitability (and speed) of resource depletion. “The greatest shortcoming of the human race,” he said, “is our inability to understand the exponential function”—that is, change that builds on previous changes. Climate change was able to creep up on most of us with cat feet because it snowballs in the same way, well, as snowballs snowball. Each subsequent change builds on the change before. The bigger it gets, the faster it grows.

Just as our brains have limits grappling with numbers, our senses have limits grasping sizes much beyond our personal, human-sized, scale, where different laws of nature dominate. Flies can walk on walls because gravity at fly scale is a barely perceptible pull, and electrical forces are everything. At the subatomic scales of quantum physics, rules change completely. Particles can be here and there simultaneously; until measured, distance, time, energy, and velocity all exist in a fuzzy state of uncertainty.

Large conglomerations of such particles, however, exhibit none of these behaviors. Our everyday world is made of emergent properties, like color, or people, or thoughts, or music. These qualities don’t exist on the scale of their most fundamental parts. They “emerge” as if out of nowhere when you get enough in one place. Even if you could somehow understand everything about every atom in your cat, you still wouldn’t know if it will purr on your lap or throw up on your carpet (or both).

Big scales are surprising for their own reasons: Where gravity rules, everything begins to look alike. Everyday objects can be square, or pointy, or flowery; but the realm of the massive is the realm of the round, because gravity crushes everything into spheres and disks. Or as the great physicist Phil Morrison so aptly put it: “No such thing as a teacup the diameter of Jupiter is possible in our world.”

Gravity on grand scales gets so bizarre it can trip up the best thinkers. When, almost 100 years ago, Einstein’s own equations of general relativity predicted that a massive enough star could implode into a black hole—leaving nothing behind but an extreme warping of spacetime—he didn’t believe it. You could say he saw black holes coming. But seeing is believing, and Einstein didn’t believe. Which is to say: Predicting the qualitative effects of quantitative changes takes more than mere genius. It takes a willingness to accept the unacceptable—something Einstein did on a regular basis. But this extrapolation went too far even for him.

Considering the trouble our brains have with big numbers and our senses have with seeing much beyond ourselves, it’s not surprising that scaling fools us. But just as Plato used a story about shadows on the wall of a cave to convey how perceptions can trick us, so scientists of today use stories to help us understand scale.

As the poet Muriel Rukeyser put it in The Speed of Darkness, “the universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” For a scientist, it is necessarily both. Scientists often have to come up with stories to translate what they see with their instruments and equations into something they—and we—can understand.

J.B.S. Haldane’s 1928 essay “On Being the Right Size” conveys the limits of our human-sized perspective beautifully, allowing us to vividly imagine how scale affects life—and why giants are impossible. Doubling the height of a person increases her volume (and mass) by a factor of eight; but since the cross-section of her bones increases only by a factor of four, merely standing could be enough to break a leg. The mass of a mouse, by comparison, is small proportional to its surface area; if it falls off a 1,000-yard-high cliff, writes Haldane, it could walk away unharmed. A cat would be killed. And a horse, he tells us, “splashes.”

Physicists certainly needed stories to convey the dangers of nuclear bombs. It was hard to make people see (even today) that they are not simply bigger bombs. They were something qualitatively different—a factor of 1,000 different. Frank Oppenheimer, Rukeyser’s schoolmate and lifelong pal, used the example of scaling up a dinner party in your home. What if you invited four people, and 4,000 appear instead? And you have to make do with the same kitchen, same pots, same glassware? This is a fair comparison, he said, because after all, the Earth itself—the people, the homes, the civilizations—does not change even as firepower increases. The introduction of nuclear weapons brought about a phase change so profound it provoked Einstein to remark: “I do not know with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.”

The physicist Bartlett, concerned with resource exhaustion, came up with a story of bacteria living in a Coke bottle. Imagine putting two bacteria in a soda bottle at 11 a.m. Assume the population doubles once every minute, and that by noon, the bottle is full. What time would it be before the bacteria-land politicians noticed that the population was running out of space? The answer is 11:59. After all, at 11:59, the bottle is still half empty! And what if the enterprising bacteria decide to drill for bottles offshore, and bring back three whole new empty bottles! How much time does that give the bacteria? Two more minutes.

In an uncanny case of “science is stranger than fiction,” it appears that real-life bacteria took lessons straight out of Bartlett’s story. That is, certain types of bacteria have developed the ability to cooperatively respond to their surroundings by using what is known as “quorum sensing.” When the bacteria reach a critical local density, they seemingly act in unison to send a signal—to glow with bioluminescence, for example, or start spewing toxic substances into our bodies that can make us very sick. The community knows when a big enough change in quantity has created a qualitatively different environment, even when individuals may not know.

Stories like these have more than mere narrative power. Following the strategy of the bacteria, perhaps social media can be used as a kind of quorum sensing, crowd-sourcing perception. It’s certainly a good way to know when a societal tipping point has been reached, and it makes rapid responses easier. Social media is also a great way to spread stories. A YouTube video of Bartlett telling his exponential growth story has been viewed 5 million times. Multiply that by a factor of even two shares with family and friends (like Bartlett’s bacteria) and you are looking at real impact.

Following the strategy of the bacteria, perhaps social media can be used as a kind of quorum sensing.

Media may already be helping us understand the economic scale changes happening in this country. The surprising success of Bernie Sanders has been propelled by online discussions of income inequality. Michael Konczal, a fellow with the Roosevelt Institute, points out that between 1980 and 2006, gross domestic product increased fivefold, while financial sector profits increased sixteenfold. Between 1984 and 2014, the increases have been fourfold and tenfold, respectively. At this rate, we could well be in for a black hole-sized phase change.

Even billionaires know something qualitatively new is going on here—something so different that the old rules don’t apply. “I’m scared,” wrote Peter Georgescu, chairman of advertising giant Young and Rubicam, in The New York Times recently, speaking of the income gap. “We risk losing the capitalist engine that brought us great economic success.” His billionaire friends are scared too, he said. They know what we’re seeing is not just more of the same.

Could a tipping point exist where a concentrated quantity of power and money really change society? Even individual behavior? The evidence is mounting. One sociological study showed that drivers of more expensive cars are less likely to stop for pedestrians than drivers of less expensive cars. Nobel laureate in economics Daniel Kahneman points to studies suggesting that “living in a culture that surrounds us with reminders of money may shape our behavior and our attitudes in ways that we do not know about and of which we may not be proud.”

We do have a way to “see it coming,” whether it’s environmental tipping points or financial ones. It’s science. The whole point of science is to penetrate the fog of human senses, including common sense. Ingenious experiments and elegant equations act as extensions of senses that allow us to see farther and more precisely—beyond the horizons of what we think we know. Calculations predict possible futures, find clear signals in the almost constant noise.

Science predicted that massive stars would implode, nuclear bombs would explode, and humans could well destroy their own habitat (if they didn’t begin to take seriously problems like overpopulation and resource depletion).

Sometimes science requires us to accept the unacceptable, certainly the unpalatable: What? Drive smaller cars? Give up my lawn? Be satisfied with a small house?

It’s not always fun to see what’s coming, especially when easy solutions are nowhere in sight. It takes courage to admit we’ve been clueless.

Then again, we really have no choice. Bartlett called people who refused to accept they lived in a closed off Coke-bottle-like world the “flat earth society”—because on a flat earth, space could be infinite. There’d be endless amounts of land for farming or garbage dumps, endless supplies of water and fuel, no limit to the amount of toxins we could pump into an infinite atmosphere.

Alas, we live on a sphere. Eratosthenes figured this out thousands of years ago, and no one liked it much then either. But he certainly saw it coming.

A professor at USC’s Annenberg School of Communication, K.C. Cole is the author of the best-seller The Universe and the Teacup: The Mathematics of Truth and Beauty, and most recently Something Incredibly Wonderful Happens: Frank Oppenheimer and his Astonishing Exploratorium.